The LGBTQ news website, “Gay Today,” is blocked in Bahrain; the website for Greenpeace International is blocked in the UAE; a matrimonial dating website is censored in Afghanistan; all of the World Health Organization’s website, including sub-pages about HIV/AIDS information, is blocked in Kuwait; an entire category of websites labeled “Sex Education,” are all censored in Sudan; in Yemen, an armed faction, the Houthis, orders the country’s main ISP to block regional and news websites.

What’s the common denominator linking these examples of Internet censorship? All of them were undertaken using technology provided by the Canadian company, Netsweeper, Inc.

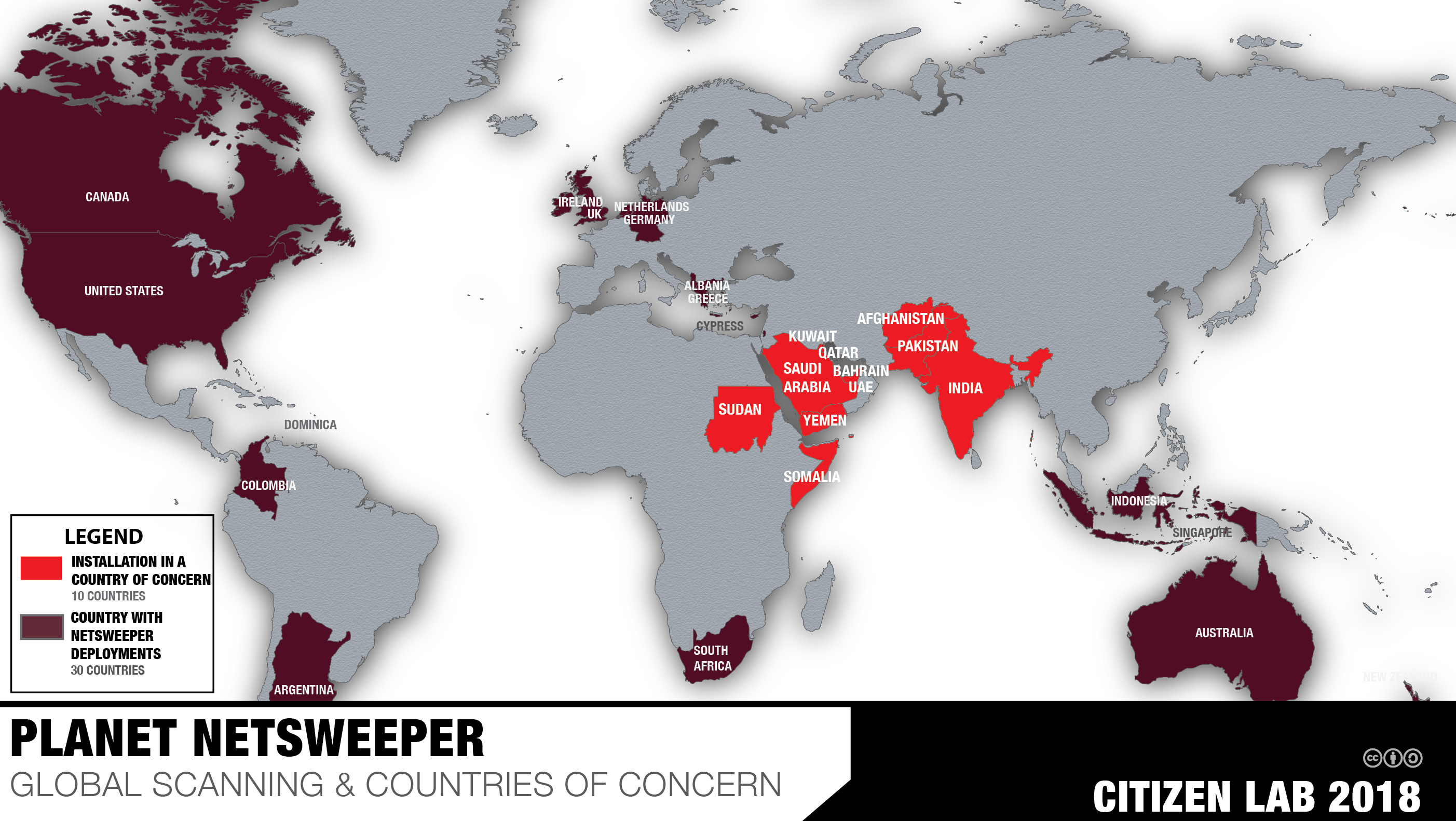

In a new Citizen Lab report published today, entitled Planet Netsweeper, we map the global proliferation of Netsweeper’s Internet filtering technology to 30 countries. We then focus our analysis on 10 countries with significant human rights, insecurity, or public policy issues in which Netsweeper systems are deployed on large consumer ISPs: Afghanistan, Bahrain, India, Kuwait, Pakistan, Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, UAE, and Yemen. The research was done using a combination of network measurement and in-country testing methods. One method involved scanning every one of the billions of IP addresses on the Internet to search for signatures we have developed for Netsweeper installations (think of it like an x-ray of the Internet).

National-level Internet censorship is a growing norm worldwide. It is also a big business opportunity for companies like Netsweeper. Netsweeper’s Internet filtering service works by dynamically categorizing Internet content, and then providing customers with options to choose categories they wish to block (e.g., “Matrimonial” in Afghanistan and “Sex Education” in Sudan). Customers can also create their own custom lists or add websites to categories of their own choosing.

Netsweeper markets its services to a wide range of clients, from institutions like libraries to large ISPs that control national-level Internet connectivity. Our report highlights problems with the latter, and specifically the problems that arise when Internet filtering services are sold to ISPs in authoritarian regimes, or countries facing insecurity, conflict, human rights abuses, or corruption. In these cases, Netsweeper’s services can easily be abused to help facilitate draconian controls on the public sphere by stifling access to information and freedom of expression.

While there are a few categories that some might consider non-controversial—e.g., filtering of pornography and spam—there are others that definitely are not. For example, Netsweeper offers a filtering category called “Alternative Lifestyles,” in which it appears mostly legitimate LGBTQ content is targeted for convenient blocking. In our testing, we found this category was selected in the United Arab Emirates and was preventing Internet users from accessing the websites of the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (http://www.glaad.org) and the International Foundation for Gender Education (http://www.ifge.org), among many others. This kind of censorship, facilitated by Netsweeper technology, is part of a larger pattern of systemic discrimination, violence, and other human rights abuses against LGBTQ individuals in many parts of the world.

According to the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, all companies have responsibilities to evaluate and take measures to mitigate the negative human rights impacts of their services on an ongoing basis. Despite many years of reporting and numerous questions from journalists and academics, Netsweeper still fails to take this obligation seriously.

As is customary for our research, we sent Netsweeper a letter prior to publication notifying them of our key findings, asking a series of questions, and offering to publish in full their response. On the positive side, this report is the first in which Netsweeper has sent a formal reply. (Their only other prior “communication” with us was a defamation suit filed against me and the University of Toronto in January 2016, and then subsequently withdrawn four months later.)

On the negative side, however, its response lacks detail and makes sweeping, dubious assertions. Rather than address our questions, Netsweeper (writing through its legal counsel) chose instead to disparage our research. It asserted that “Mr. Diebert’s [sic] analysis and conclusions, as well as representations he has made before Parliament, are alarming for the real absence of any sound technical understanding on how internet providers operate, how information technology companies support online operations, and how online programs function.” The careful methods we used to undertake our research are exceedingly well-detailed in Section 1 of our report, and so we will leave it for knowledgeable readers to draw their own conclusions.

Strangely, Netsweeper also asserts that “The ultimate effect of what Mr. Diebert [sic] and his interests propose would be the full-scale shut down of the internet in multiple jurisdictions worldwide.” In fact, by encouraging more transparency, accountability, and proportionality around Internet censorship, we are aiming to do precisely the opposite.

Our report also suggests Canada could be doing more. It should go without saying that the use of Canadian technology by authoritarian and other regimes to undertake Internet censorship undercuts Canada’s own foreign policy and commitment to human rights. The Trudeau Government has prioritized an international stance that promotes “gender equality,” and yet here we have the services of a Canadian company employed to do the exact opposite on behalf of the some of the world’s most illiberal regimes. Worse, both the Government of Canada and some Provincial Government entities have actually facilitated Netsweeper’s exports through grants and other forms of assistance, which we document in the report.

To be more consistent with its own policies and obligations, we suggest the Canadian government could take measures to prevent these types of human rights violations, including tying whatever government support is provided to clear prohibitions against activities that undermine human rights, and effective and ongoing due diligence, public transparency reporting, and other accountability measures. Canada could also strengthen the control of exports for Internet censorship and surveillance services, and focus transparency and accountability efforts on the “dual-use” technology sector through the newly created Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise (CORE).

Access to information is a human right recognized under international law — yet one that many governments defy in practice through extensive Internet censorship. By facilitating these practices, Netsweeper is profiting from the dark curtain being drawn over the Internet for a large number of users around the world.