Ronald Deibert

Director of The Citizen Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto

Ronald J. Deibert is a professor of political science at the University of Toronto and the founder and director of The Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto.

> For Students

> Publications

> Contact

-

The Real Lesson of SignalGate

“We are currently clean on OPSEC.” Those infamous words, typed by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth into a Signal group created by White House National Security Advisor Mike Waltz to coordinate U.S. airstrikes in Yemen, could not have been further…

-

Paragon’s Spyware: A first look at infrastructure, customers and victims

The Citizen Lab published the first reports on the abuse of numerous mercenary spyware firms’ products, including Gamma Group (2012), Hacking Team (2012), Dark Matter (Stealth Falcon) (2016), NSO Group (2016), Cyberbit (2017), Circles (2020), Candiru (2021), Cytrox’s Predator (2021), and Quadream (2023). And now here we are with yet another first: a report on Paragon Solutions. Founded in Israel in 2019, Paragon sells a spyware product called Graphite, which reportedly…

-

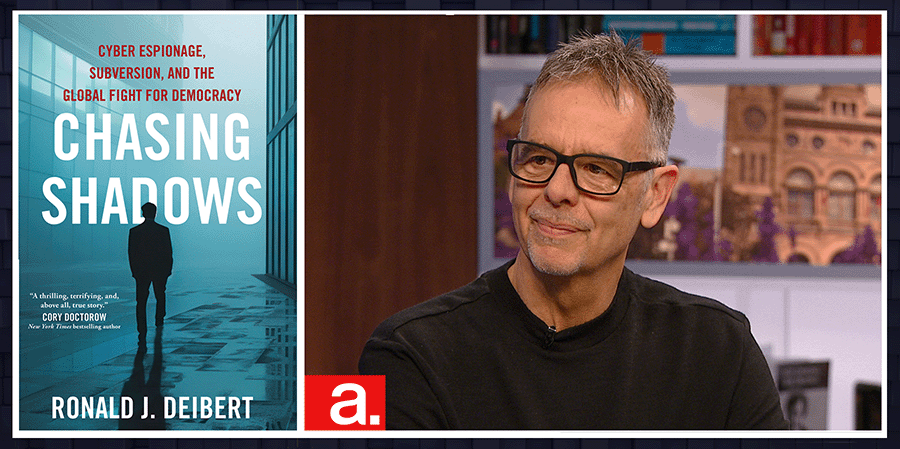

Chasing Shadows is a National Bestseller!

Thanks everyone who has picked up a copy of Chasing Shadows and helped make it a national bestseller in Canada! UPCOMING APPEARANCES Wednesday March 5th: International Spy Museum, Washington DC (with Ellen Nakashima of the Washington Post). Details: https://www.spymuseum.org/calendar/chasing-shadows-with-ronald-deibert-and-ellen-nakashima/2025-03-05/ Monday March 10th: City Lights Bookstore, San Francisco, CA (with Eva Galperin and Cindy Cohn of…

-

Silenced by Surveillance

What obligations do countries have to protect those living in their borders from the growing scourge of digital transnational repression? That’s the question Citizen Lab senior legal advisor Siena Anstis and I explain in our new essay for the Knight First Amendment Institute, entitled: “Silenced by Surveillance: The Impacts of Digital Transnational Repression on Journalists,…

-

On Sale Now: Chasing Shadows

Well it has been a long time coming but I am super excited to share with you that my new book, Chasing Shadows, is on sale today! The book is a true David vs Goliath story (or, perhaps more accurately, David vs many Goliaths). It was a real labour of love to recount the story of the Citizen…

-

Jail Time for Private Detective

Private detective who led a hacking operation against climate activists, short sellers and others sentenced Several years ago, we investigated a sprawling hack-for-hire operation targeting a cross section of civil society, lawyers, journalists, activists, & short sellers. That investigation resulted in the 2020 Citizen Lab report, Dark Basin: Uncovering a Massive Hack-For-Hire Operation. Now, a key…

RONALD DEIBERT

Director, The Citizen Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto