It’s often remarked that digital espionage can be undertaken on the cheap. But just how cheap?

In a new Citizen Lab report released this morning, we give one answer. Taking advantage of simple errors committed by the operator of a phishing operation, we were able to get an “inside view” of just what it takes to mount an effective digital spying job.

For more than 8 months, we quietly observed as the operator set up phishing lures, registered decoy domains disguised as popular email services, made fake login pages, sent targeted emails to individuals and organizations, and maintained the back-end infrastructure for the entire enterprise.

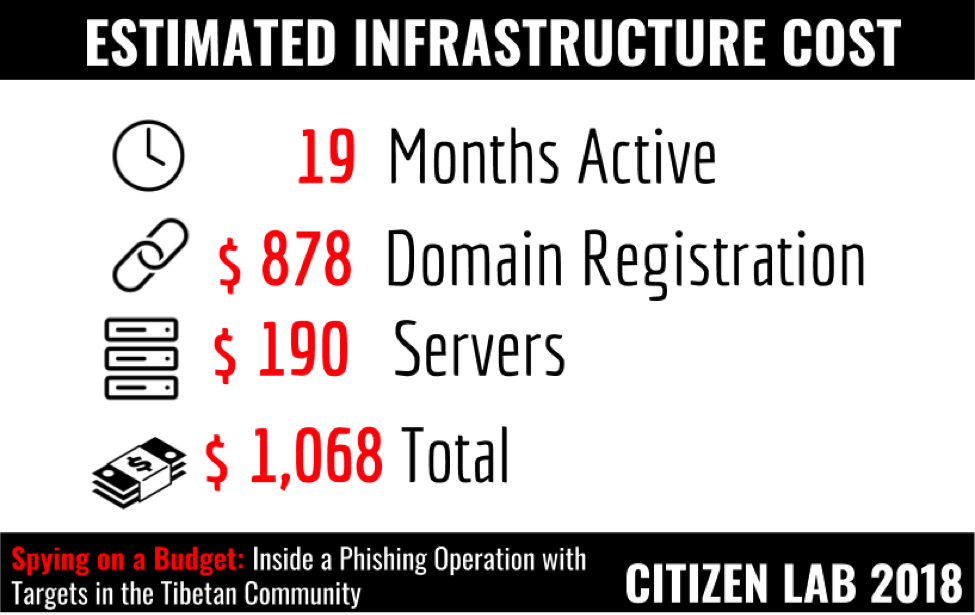

Total estimated cost: $1,068.00

Running this operation would require only basic system administration and web development skills and although it was sloppy in execution, the phishing campaign was nonetheless successful. At least two accounts we tracked were compromised, with contact lists stolen from the victims used to send out more phishing emails to other targets. We suspect there were likely other successful compromises beyond these accounts based on decoy documents we collected that appear to be private files likely extracted from compromised accounts.

Who was behind it? While we have no evidence linking the individual(s) running it to a specific government agency or other client, there are a number of clues as to its motivation and possible benefactor. The bulk of activity we observed was focused on Tibetan organizations, and we were able to verify this targeting with the cooperation of individuals and organizations involved in Tibet-related activism who shared with us phishing emails they received from the operator.

But the operator was interested in more than Tibet. Our analysis of decoy documents, phishing pages, and registered domains used in the operation shows several non-Tibetan themes that suggest there were other targets. These themes include the Uyghur ethnic minority group, Epoch Times (a media group founded by members of the persecuted religious organization Falun Gong), themes related to Hong Kong, Burma, the Pakistan Army, the Sri Lankan Ministry of Defence, the Thailand Ministry of Justice, and a controversial Chinese billionaire critical of state corruption.

Add these up and the common denominator uniting them all is that they fall within the strategic interest of the People’s Republic of China. While we have no evidence to show the operator was working on behalf of a specific Chinese government agency, it’s well known that freelancers and security contractors do so on a regular basis. In November 2017, for example, the US Department of Justice indicted three Chinese nationals working at an Internet security firm for digital theft of commercial secrets. (One wonders what it will take to marshall the political will to bring such an indictment against an individual for hacking a human rights organization). Although the indictment didn’t say so, it’s reported that the Internet security firm (Boyusec) is ultimately working on behalf of the Chinese Ministry of State Security. Such arms-length relationships are beneficial to the state, which can reap the fruits of espionage while retaining a certain degree of plausible deniability.

The sloppiness of the operator may also be suggestive. Who ever was behind this campaign may have just been amateurs who made mistakes. Or they may also have been operating on the assumption that their actions were, if not condoned by some higher authority, then at least implicitly tolerated. In other words: operational security may be inversely correlated with fear of consequences, And in China there are, at present, very few consequences of running a hacking operation for hire — whether the targets are a foreign company’s intellectual property assets or a NGO’s strategic communications plans. Why worry about operational security if getting caught doesn’t matter?

The case also illustrates yet another important lesson: digital espionage operations will only be as sophisticated and expensive in their execution as what it takes for them to work. Someone is not going to bother spending more time and money than necessary if something “on the cheap” like this setup will do the job just as well.

But there’s a flip side to this lesson, one that we hope individuals and organizations will pick up upon in their digital security planning: simple phishing operations can also be simply blunted. The successful compromises would likely have never happened had the individuals and organizations in question implemented two-factor authentication — a security feature that requires a second ‘factor’ (like a code on a mobile phone) to access an account. Unfortunately, two-factor authentication is still far from being widely adopted by many users, and is not on by default in almost all popular online platforms.

We need to start thinking of two-factor authentication as the equivalent of a “seat belt” for the Internet: not perfect, but it may help mitigate the impact of a digital crash. Major platform providers should mainstream security features like two factor authentication into their services to help limit the harm done by inexpensive but effective phishing. And just as with seat belts and automobile manufacturers, if the companies can’t do it themselves, perhaps it’s time that regulators step in and require that it be done.

Read the full report here: Spying on a Budget: Inside Phishing Operation with Targets in the Tibetan Community.

Also, check out a few of our digital security resources to learn more about two factor authentication and other ways to protect yourself online at Net Alert and Security Planner.